MA Early Modern History student at The University of Sheffield, specialising in Caribbean slavery in the 17th & 18th centuries.

📸 Instagram: @historian_noor

#SkyStorian #SkyStorians #AcademicSky

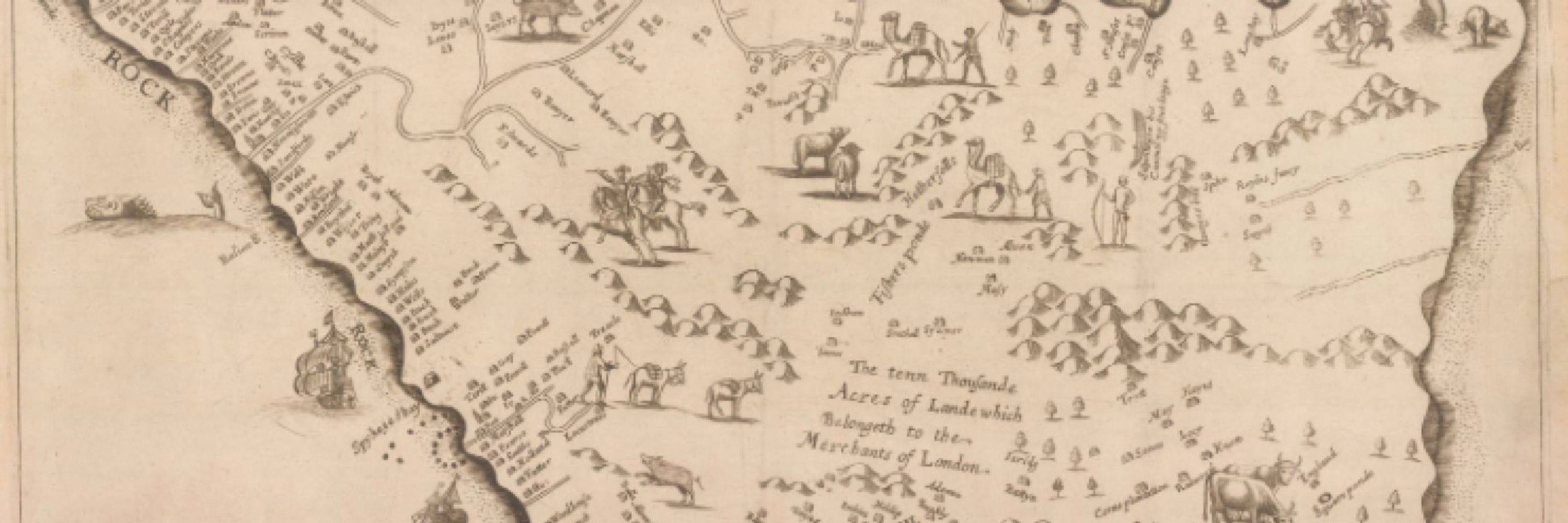

There is so much that can be gleaned from this source alone. My post discusses some of the features!

To mark the occasion, eleven historians share how they've used the journal in their own teaching.

To mark the occasion, eleven historians share how they've used the journal in their own teaching.

alanlester.co.uk/blog/antisla...

alanlester.co.uk/blog/antisla...

MERRY CHRISTMAS EVERYONE! 🎄💝 ft. one of my favourite Xmas songs from one of my favourite artists ever🥂

MERRY CHRISTMAS EVERYONE! 🎄💝 ft. one of my favourite Xmas songs from one of my favourite artists ever🥂

For which I began research in 2006.

Is now posted on the website for Princeton University Press.

Cover will be added soon.

The King’s Slaves: The British Empire & the Origins of American Slavery

For which I began research in 2006.

Is now posted on the website for Princeton University Press.

Cover will be added soon.

The King’s Slaves: The British Empire & the Origins of American Slavery

'The Historian in the Age of AI' by @chriscampbell1.bsky.social.

New Comment article now available in 'Transactions of the Royal Historical Society' bit.ly/4atErTB #Skystorians 1/2

'The Historian in the Age of AI' by @chriscampbell1.bsky.social.

New Comment article now available in 'Transactions of the Royal Historical Society' bit.ly/4atErTB #Skystorians 1/2

There is so much that can be gleaned from this source alone. My post discusses some of the features!

There is so much that can be gleaned from this source alone. My post discusses some of the features!

Personally, the fact that thousands of UK adults are unaware of Britain’s role in the slave trade makes me feel uncomfortable.

How disappointing.

Personally, the fact that thousands of UK adults are unaware of Britain’s role in the slave trade makes me feel uncomfortable.

How disappointing.

I have made an Instagram account for all things history/research related! I’ll still be on here, but do give me a follow on the other place if you wish. I’ll be posting on there every now and again! 😊

I have made an Instagram account for all things history/research related! I’ll still be on here, but do give me a follow on the other place if you wish. I’ll be posting on there every now and again! 😊

We should make sure that anyone of that surname should not be allowed within a mile of the building.

We should make sure that anyone of that surname should not be allowed within a mile of the building.

I have made an Instagram account for all things history/research related! I’ll still be on here, but do give me a follow on the other place if you wish. I’ll be posting on there every now and again! 😊

I have made an Instagram account for all things history/research related! I’ll still be on here, but do give me a follow on the other place if you wish. I’ll be posting on there every now and again! 😊

Just a month to go before @uclpress.bsky.social publishes this open access (free to download) expert volume. uclpress.co.uk/book/teachin...

Just a month to go before @uclpress.bsky.social publishes this open access (free to download) expert volume. uclpress.co.uk/book/teachin...

🔒 This feature from the October issue is available in the archive

www.historytoday.com/archive/feat...

🔒 This feature from the October issue is available in the archive

www.historytoday.com/archive/feat...

🌎 Archives across the Atlantic: Unearthing Black History. A conversation with the University of Rochester ( 🗓️ Thursday 23 October at 🕓 4pm BST / 🕚 11am EDT)

leeds.libcal.com/calendar/ope...

🌎 Archives across the Atlantic: Unearthing Black History. A conversation with the University of Rochester ( 🗓️ Thursday 23 October at 🕓 4pm BST / 🕚 11am EDT)

leeds.libcal.com/calendar/ope...

The survey, known as the Valor Ecclesiasticus, set out to discover the financial state of the Church'.

The survey, known as the Valor Ecclesiasticus, set out to discover the financial state of the Church'.

memorients.com/articles/tan...

memorients.com/articles/tan...

The menu booklet for what would be the final lunch onboard the Titanic.

The menu booklet for what would be the final lunch onboard the Titanic.

@time.com

time.com/7319963/bruc...

@time.com

time.com/7319963/bruc...