Corey Cusimano

@cusimano.bsky.social

Assistant Professor of Marketing at Yale University.

I study how people think about thinking, and how people think about justice.

Website: www.coreycusimano.net

I study how people think about thinking, and how people think about justice.

Website: www.coreycusimano.net

That's just two possibilities. There are a ton of others that my coauthors and I have thought about.

But we haven't actually tested entitlement in students yet. Do either of those possibilities resonate with you? Or, do you have any other ideas?

But we haven't actually tested entitlement in students yet. Do either of those possibilities resonate with you? Or, do you have any other ideas?

May 9, 2025 at 7:04 PM

That's just two possibilities. There are a ton of others that my coauthors and I have thought about.

But we haven't actually tested entitlement in students yet. Do either of those possibilities resonate with you? Or, do you have any other ideas?

But we haven't actually tested entitlement in students yet. Do either of those possibilities resonate with you? Or, do you have any other ideas?

Or, maybe these students don't *really* feel entitled to a higher grade, they just think they can *get* one by appealing to effort. When I show these kinds of students how much better other students performed relative to them, they typically drop their appeals.

May 9, 2025 at 7:04 PM

Or, maybe these students don't *really* feel entitled to a higher grade, they just think they can *get* one by appealing to effort. When I show these kinds of students how much better other students performed relative to them, they typically drop their appeals.

One thing that might be going on is that students who work hard think that their performance actually is better than the teacher says it is. (After all, overachievers are used to their hard work resulting in high performance.) So, the appeals could be about performance (deep down).

May 9, 2025 at 7:04 PM

One thing that might be going on is that students who work hard think that their performance actually is better than the teacher says it is. (After all, overachievers are used to their hard work resulting in high performance.) So, the appeals could be about performance (deep down).

Hi Dave! I totally share your intuition here. It is possible that students feel differently about their grades than adults feel about, e.g., pay and bonuses.

But, maybe the student case isn't such a clear counter-example either. I'm curious what you think:

But, maybe the student case isn't such a clear counter-example either. I'm curious what you think:

May 9, 2025 at 7:04 PM

Hi Dave! I totally share your intuition here. It is possible that students feel differently about their grades than adults feel about, e.g., pay and bonuses.

But, maybe the student case isn't such a clear counter-example either. I'm curious what you think:

But, maybe the student case isn't such a clear counter-example either. I'm curious what you think:

When we started, we expected the opposite results: Hard work marks us as virtuous. Achievement, even though it creates value for others, is often a product of luck.

Our intuitive sense of entitlement may not care about how lucky we are, only whether we succeed at the work we do for others.

Our intuitive sense of entitlement may not care about how lucky we are, only whether we succeed at the work we do for others.

May 8, 2025 at 9:51 PM

When we started, we expected the opposite results: Hard work marks us as virtuous. Achievement, even though it creates value for others, is often a product of luck.

Our intuitive sense of entitlement may not care about how lucky we are, only whether we succeed at the work we do for others.

Our intuitive sense of entitlement may not care about how lucky we are, only whether we succeed at the work we do for others.

These findings were robust!

Workers paid themselves based on outcomes (not effort) even when they knew that others weren't working as hard as they were.

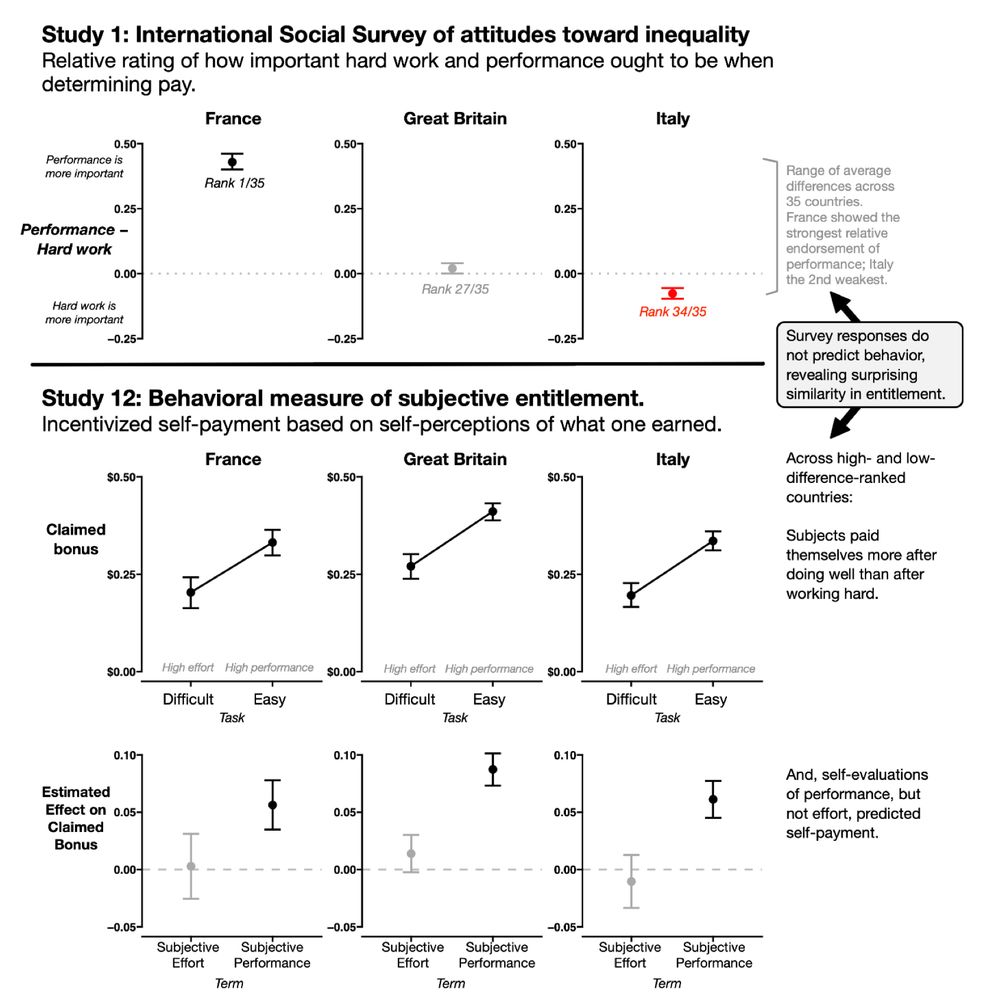

We also replicated this result across cultures who, in other surveys, appear to differ in the value of hard work and achievement.

Workers paid themselves based on outcomes (not effort) even when they knew that others weren't working as hard as they were.

We also replicated this result across cultures who, in other surveys, appear to differ in the value of hard work and achievement.

May 8, 2025 at 9:51 PM

These findings were robust!

Workers paid themselves based on outcomes (not effort) even when they knew that others weren't working as hard as they were.

We also replicated this result across cultures who, in other surveys, appear to differ in the value of hard work and achievement.

Workers paid themselves based on outcomes (not effort) even when they knew that others weren't working as hard as they were.

We also replicated this result across cultures who, in other surveys, appear to differ in the value of hard work and achievement.

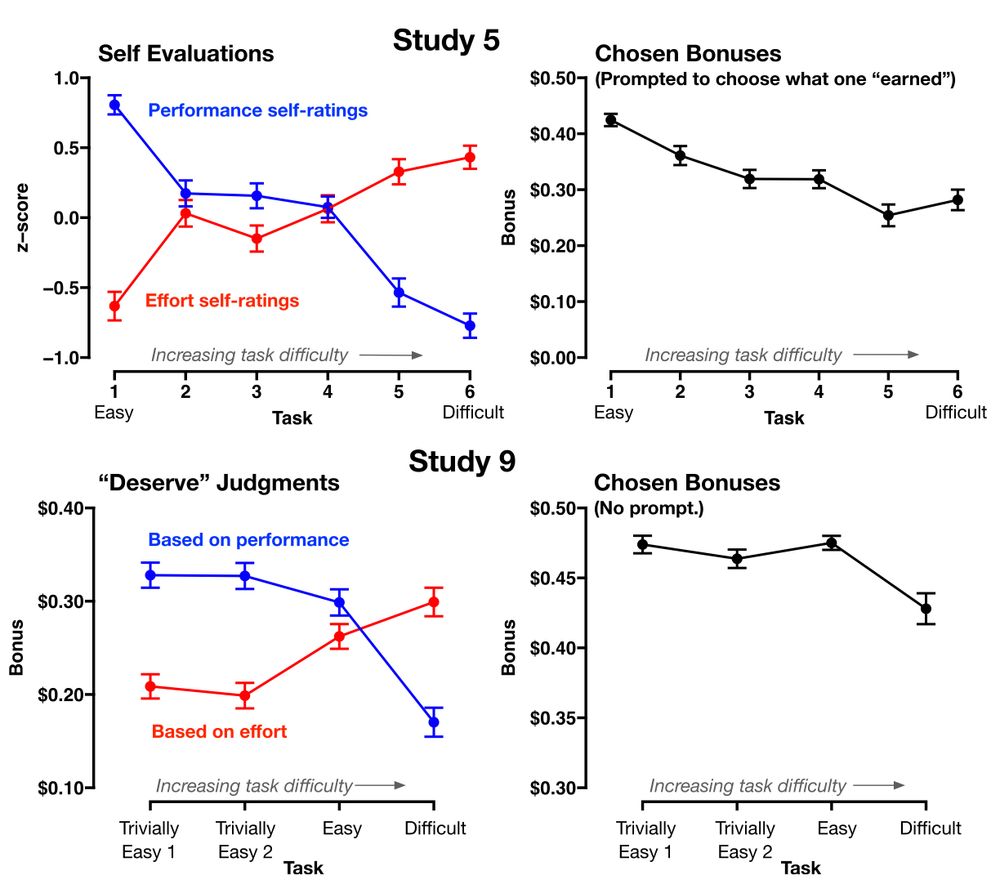

We gave online workers short jobs to do. We varied how much effort the job induced, and how good a job the workers could do on it.

We then let workers choose their bonus for their work (which we then paid them).

Workers paid themselves based on how good they did, not how hard they worked.

We then let workers choose their bonus for their work (which we then paid them).

Workers paid themselves based on how good they did, not how hard they worked.

May 8, 2025 at 9:51 PM

We gave online workers short jobs to do. We varied how much effort the job induced, and how good a job the workers could do on it.

We then let workers choose their bonus for their work (which we then paid them).

Workers paid themselves based on how good they did, not how hard they worked.

We then let workers choose their bonus for their work (which we then paid them).

Workers paid themselves based on how good they did, not how hard they worked.