Brings tears to the eyes of a true PD-nerd 🎓🎓🎓

Brings tears to the eyes of a true PD-nerd 🎓🎓🎓

![Forest plot showing 95% confidence intervals for UF rate, free water transport, diffusion capacity (MTAC) for 18F-deoxyglucose ([18-F]-DG), and MTACs for glucose, creatinine, urea and potassium.](https://cdn.bsky.app/img/feed_thumbnail/plain/did:plc:mlm2rmhobpzknkridc7qmz2b/bafkreib6v2su3adcdcudd47bwrabz6rr74zygxzx7ne6rpiztldwhirg5u@jpeg)

Original Article - journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10....

Editorial - @johannmorelle.bsky.social @carloberg.bsky.social journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10....

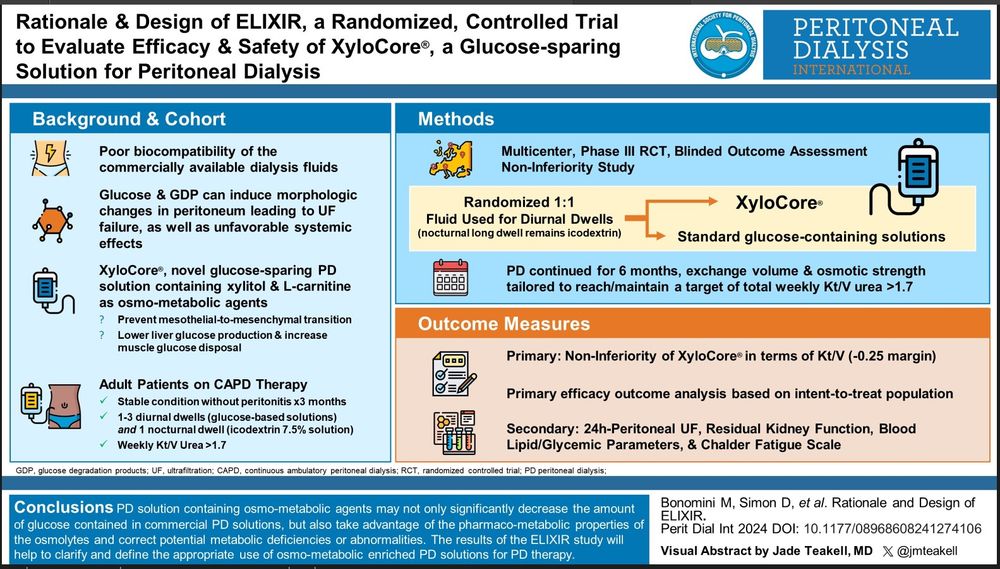

VA - @jmteakell.bsky.social