Dow Medical College | Head Research Analyst @ RCOP | Biostatistician | Aspiring Cardiologist | Polymath

📖 Full study: doi.org/10.1016/j.cp...

We have evidence-based treatments that work, but only when patients can access quality care consistently.

This points to social and environmental factors we can actually address.

This isn't about individual choices, it's about how the healthcare system delivers care.

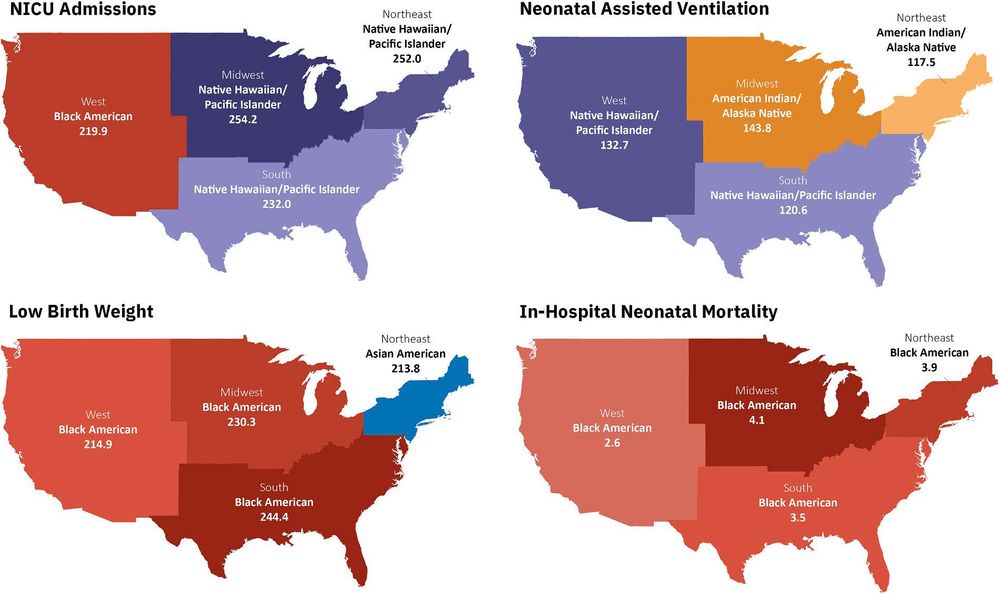

- Low birth weight: 235.1 per 1,000 (Black) vs 121.8 per 1,000 (White)

- NICU admissions: 217.2 per 1,000 (Black) vs 156.0 per 1,000 (White)

- Regional patterns: Midwest and South consistently worse

These disparities held even after controlling for maternal age, diabetes, smoking, and BMI.

Our new study in Current Problems in Cardiology analyzed every birth to hypertensive mothers in the US (2016-2022).

Thread 👇

#MedSky

It’s about the care people get in their final days, and who’s left behind.

📖 Read the full study:

doi.org/10.1161/CIRC...

#CardioSky #MedSky #AHAJournals #Cardiology #HeartFailure #PalliativeCare #HealthEquity #EndOfLifeCare

They reflect patterns — in access, trust, and structural care gaps.

📍 Place of death is a proxy:

For dignity.

For inequity.

For how systems succeed — or fall short.

🧑🎓 Age (20–34):

• 56.2% died in hospitals

👨 Men:

• 37% less likely to die in hospice

🧑🏿 Black adults:

• 61% more likely to die in ED/outpatient

• 47% less likely to receive hospice

📍 Rural/small metro:

• More likely to die in hospice (ORs: 1.21, 1.09)

Hospice/nursing home deaths:

• Peaked in 2017 at 34.7%

• Dropped to 29.5% by 2023

➤ 5.2-point fall in just 6 years

This decline started before COVID.

What changed?

In 1999:

• Hospital = 45.1%

• Home = 18.4%

By 2023:

• Hospital = 32.4%

• Home = 33.5%

A shift toward home — but is it a supported choice, or a system gap?

And the U.S. healthcare system is quietly rewriting that story.

We analyzed 7.6 million death certificates (1999–2023) to find out where adults with heart failure spend their final days.

What we found raises hard questions.

We can — and must — do better.

✅ Define what “better” really means

📊 Measure who improves — and for how long

⚰️ Count everyone — including those who die

🧪 Test treatments in real-world populations

📄 Full paper: www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/...

Trials often enroll younger, healthier folks.

But in the real world, heart failure hits older, sicker adults.

If it works in a trial, will it work for your patients?

KCCQ can’t be filled out by people who die.

So some trials exclude them from the results.

If more people die on a drug… shouldn’t that count?

A drug that makes you feel better for 2 weeks — then stops?

Most trials don’t thoroughly check if KCCQ improvements are durable.

Shouldn’t we be asking that before approval?

If the average KCCQ gain is 3 points… who’s getting better?

Maybe a few patients feel great, others feel nothing.

Averages don’t tell us who benefits — and that’s what matters.

Trials say a 5-point KCCQ boost is meaningful.

But newer data? Patients may need 10–16 points to actually feel a difference.

So are we approving drugs that don’t help enough?

In our new @ahajournals.bsky.social paper, we dig into how patient-reported outcomes (like KCCQ) are used — and what may be going wrong. 🧵

#CardioSky #MedSky #Circulation #AHAJournals #Cardiology

We accept statins for primary prevention based on subgroup data…

So why do we treat SGLT-2 inhibitors differently?

What are we waiting for? A perfect RCT? In the meantime, patients are dying without optimal treatment.

✔️ True—most trials focus on younger patients and only include older adults in subgroup analyses.

✔️ But does that justify withholding a therapy that consistently reduces mortality & hospitalizations?

✔️ 12% drop in all-cause mortality (RR 0.88, 95% CI: 0.83–0.95)

✔️ 18% lower CV death (RR 0.82, 95% CI: 0.74–0.92)

✔️ 28% fewer heart failure hospitalizations (RR 0.72, 95% CI: 0.66–0.79)

✔️ Lower serious adverse events overall (RR 0.92, 95% CI: 0.89–0.95)

Our meta-analysis (32,541 older adults) shows SGLT-2 inhibitors significantly reduce mortality, heart failure hospitalizations, and major cardiac events.

Yet, they remain underused. Why? 🧵👇

#CardioSky

💡 We also found underweight & normal-weight groups had the longest median LOS (5 days), while overweight patients accrued the highest total charges (~$53K). Check out the full article below 📖

journals.lww.com/coronary-art...

🔍 After adjusting for confounders, underweight status was linked to higher mortality (OR=1.38) vs. normal weight, while overweight/obesity showed lower odds (e.g., class I obesity OR=0.54). Could a higher BMI be protective in #CAD?