Youngki Hong

@youngkihong.bsky.social

Job alert: I'm hiring a postdoc for my lab at CU Boulder starting Fall 2026!

We study person perception, stereotyping & prejudice, and intervention science using behavioral & neuroimaging methods.

Link: jobs.colorado.edu/jobs/JobDeta...

Review starts Nov 1 and continues until filled.

We study person perception, stereotyping & prejudice, and intervention science using behavioral & neuroimaging methods.

Link: jobs.colorado.edu/jobs/JobDeta...

Review starts Nov 1 and continues until filled.

Postdoctoral Associate

jobs.colorado.edu

September 10, 2025 at 6:35 AM

Together, these studies support a simple idea:

The self is a representational base.

When imagining what “us” looks like, people lean on who they are and how they see themselves.

(5/5)

The self is a representational base.

When imagining what “us” looks like, people lean on who they are and how they see themselves.

(5/5)

September 1, 2025 at 4:43 PM

Together, these studies support a simple idea:

The self is a representational base.

When imagining what “us” looks like, people lean on who they are and how they see themselves.

(5/5)

The self is a representational base.

When imagining what “us” looks like, people lean on who they are and how they see themselves.

(5/5)

Study 3: We used OpenFace to test whether people were just matching based on trustworthiness. Even after accounting for perceived trustworthiness, ingroup faces were objectively more similar to their creators, confirming a role for self-image.

(4/5)

(4/5)

September 1, 2025 at 4:43 PM

Study 3: We used OpenFace to test whether people were just matching based on trustworthiness. Even after accounting for perceived trustworthiness, ingroup faces were objectively more similar to their creators, confirming a role for self-image.

(4/5)

(4/5)

Study 2: Ingroup faces resembled their creators. An independent sample could match ingroup faces to photographs of the people who generated them better than chance, suggesting self-image guided the visual representations.

(3/5)

(3/5)

September 1, 2025 at 4:43 PM

Study 2: Ingroup faces resembled their creators. An independent sample could match ingroup faces to photographs of the people who generated them better than chance, suggesting self-image guided the visual representations.

(3/5)

(3/5)

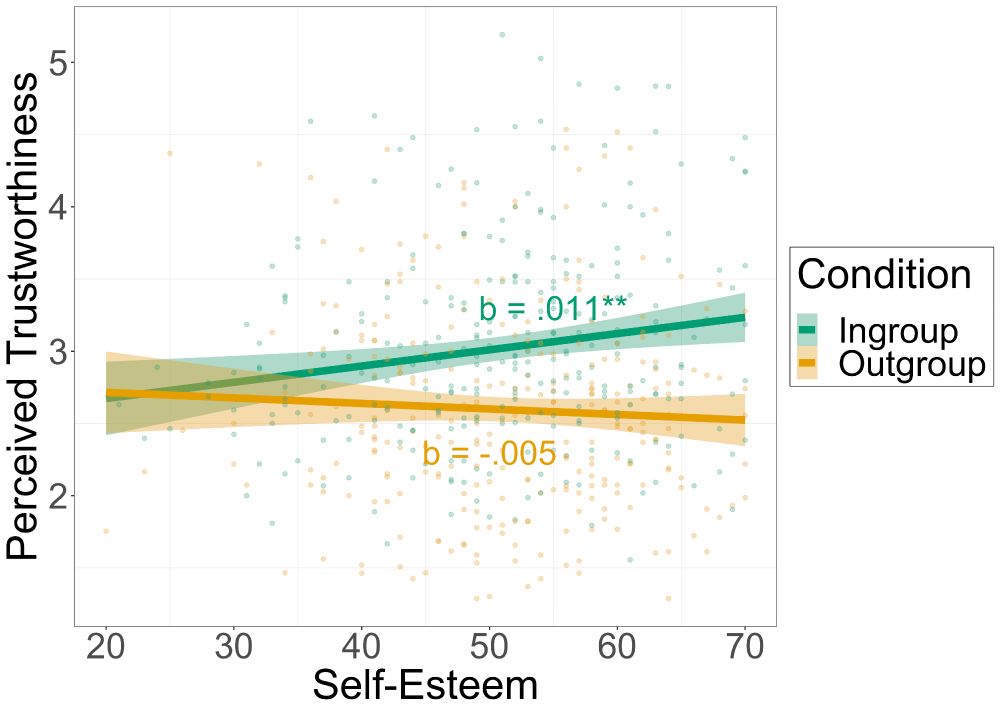

Study 1: People with higher self-esteem generated ingroup faces that were perceived as more trustworthy to others. Self-evaluation shaped how “us” looked even in novel group settings.

(2/5)

(2/5)

September 1, 2025 at 4:43 PM

Study 1: People with higher self-esteem generated ingroup faces that were perceived as more trustworthy to others. Self-evaluation shaped how “us” looked even in novel group settings.

(2/5)

(2/5)

We asked:

How do people visualize others in new groups, even with no shared history or traits?

Using the minimal group paradigm + reverse correlation methods, we tested if self-image and self-esteem shape mental representations of ingroup faces.

(1/5)

How do people visualize others in new groups, even with no shared history or traits?

Using the minimal group paradigm + reverse correlation methods, we tested if self-image and self-esteem shape mental representations of ingroup faces.

(1/5)

September 1, 2025 at 4:43 PM

We asked:

How do people visualize others in new groups, even with no shared history or traits?

Using the minimal group paradigm + reverse correlation methods, we tested if self-image and self-esteem shape mental representations of ingroup faces.

(1/5)

How do people visualize others in new groups, even with no shared history or traits?

Using the minimal group paradigm + reverse correlation methods, we tested if self-image and self-esteem shape mental representations of ingroup faces.

(1/5)

Overall takeaway: Sound symbolism can shape trait inferences about groups. But when groups are self-relevant and competitive, these effects can weaken or even reverse.

This research suggests that phonemic cues are not inert; they interact with intergroup processes in meaningful ways. (7/7)

This research suggests that phonemic cues are not inert; they interact with intergroup processes in meaningful ways. (7/7)

July 11, 2025 at 7:48 PM

Overall takeaway: Sound symbolism can shape trait inferences about groups. But when groups are self-relevant and competitive, these effects can weaken or even reverse.

This research suggests that phonemic cues are not inert; they interact with intergroup processes in meaningful ways. (7/7)

This research suggests that phonemic cues are not inert; they interact with intergroup processes in meaningful ways. (7/7)

In Study 3, we merely assigned participants to groups without the competitive framing. Sound symbolism effects on group perception reemerged. However, sound–shape congruence rates were still lower than in the no-group condition in Study 1. (6/7)

July 11, 2025 at 7:48 PM

In Study 3, we merely assigned participants to groups without the competitive framing. Sound symbolism effects on group perception reemerged. However, sound–shape congruence rates were still lower than in the no-group condition in Study 1. (6/7)

What do we mean by reversal? Some participants matched Bouba/Maluma with the sharp shape and Kiki/Takete with the round shape (the reverse of the expected mapping). Those same participants then rated round-sounding groups as more dominant, confident, and sociable than sharp-sounding groups. (5/7)

July 11, 2025 at 7:48 PM

What do we mean by reversal? Some participants matched Bouba/Maluma with the sharp shape and Kiki/Takete with the round shape (the reverse of the expected mapping). Those same participants then rated round-sounding groups as more dominant, confident, and sociable than sharp-sounding groups. (5/7)

In Study 2, participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups (Bouba vs. Kiki) and completed a resource competition task. Participants rated their own group more favorably, regardless of the name. Sound symbolism effects were absent or reversed. (4/7)

July 11, 2025 at 7:48 PM

In Study 2, participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups (Bouba vs. Kiki) and completed a resource competition task. Participants rated their own group more favorably, regardless of the name. Sound symbolism effects were absent or reversed. (4/7)

In Study 1, for example, participants rated groups with round-sounding names (Bouba, Maluma) as more trustworthy and caring. Groups with sharp-sounding names (Kiki, Takete) were rated as more dominant and extraverted. (3/7)

July 11, 2025 at 7:48 PM

In Study 1, for example, participants rated groups with round-sounding names (Bouba, Maluma) as more trustworthy and caring. Groups with sharp-sounding names (Kiki, Takete) were rated as more dominant and extraverted. (3/7)

Across three studies, we found that sound symbolism can influence perceptions of novel groups. But categorization into groups and intergroup competition can diminish, override, or even reverse these effects. (2/7)

July 11, 2025 at 7:48 PM

Across three studies, we found that sound symbolism can influence perceptions of novel groups. But categorization into groups and intergroup competition can diminish, override, or even reverse these effects. (2/7)

The Bouba–Kiki effect is a well-documented phenomenon in sound symbolism. People reliably associate round-sounding words like “Bouba” with round shapes and sharp-sounding words like “Kiki” with angular shapes. We asked: What happens when those sounds are used as group names? (1/7)

July 11, 2025 at 7:48 PM

The Bouba–Kiki effect is a well-documented phenomenon in sound symbolism. People reliably associate round-sounding words like “Bouba” with round shapes and sharp-sounding words like “Kiki” with angular shapes. We asked: What happens when those sounds are used as group names? (1/7)