This suggests dynamical forces may be playing a role in many other developmental processes, too. We should look!

13/n

This suggests dynamical forces may be playing a role in many other developmental processes, too. We should look!

13/n

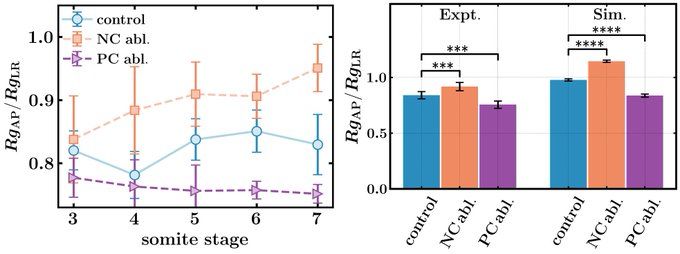

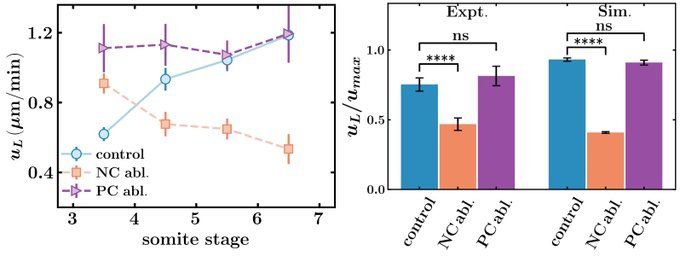

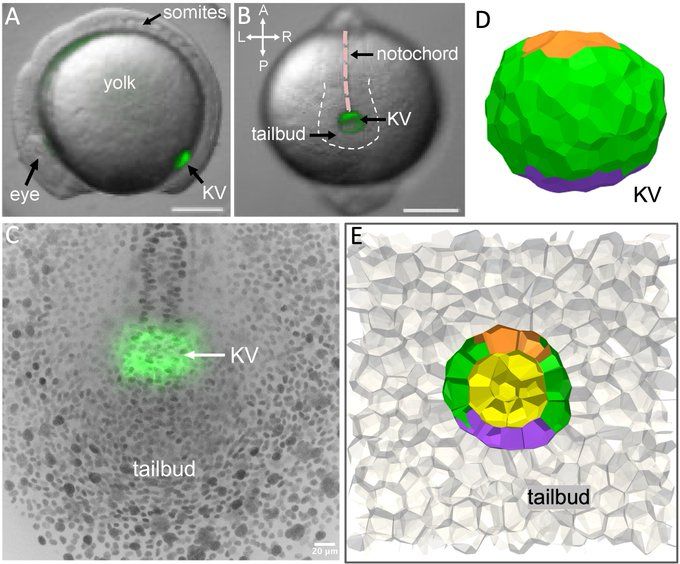

Yes, notochord ablation reduces the AP distribution as compared to controls. The 3D vertex model predicts this.

12/n

Yes, notochord ablation reduces the AP distribution as compared to controls. The 3D vertex model predicts this.

12/n

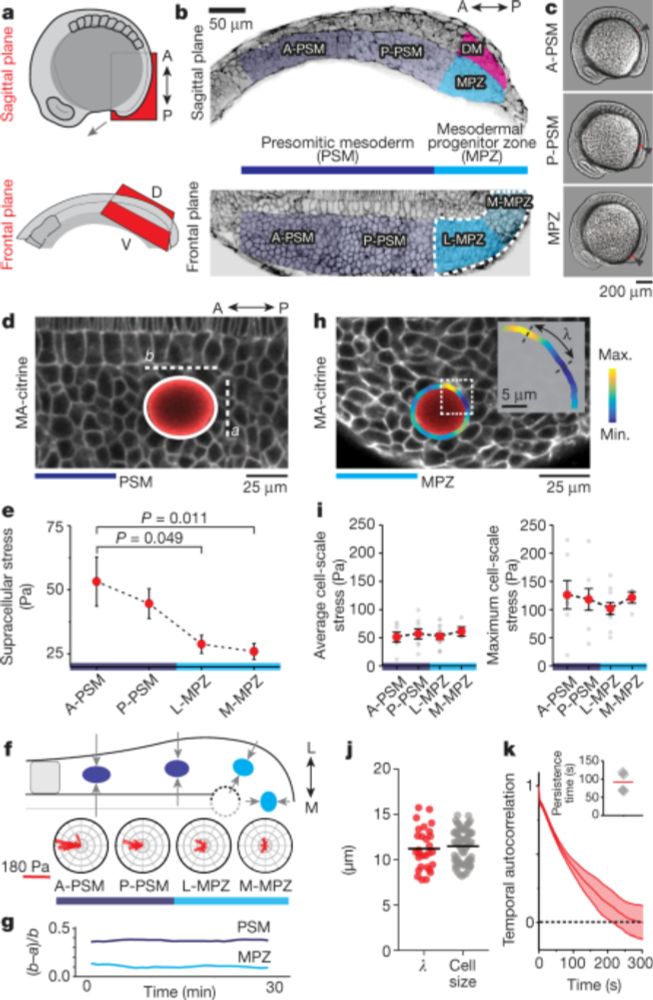

11/n

11/n

10/n

10/n

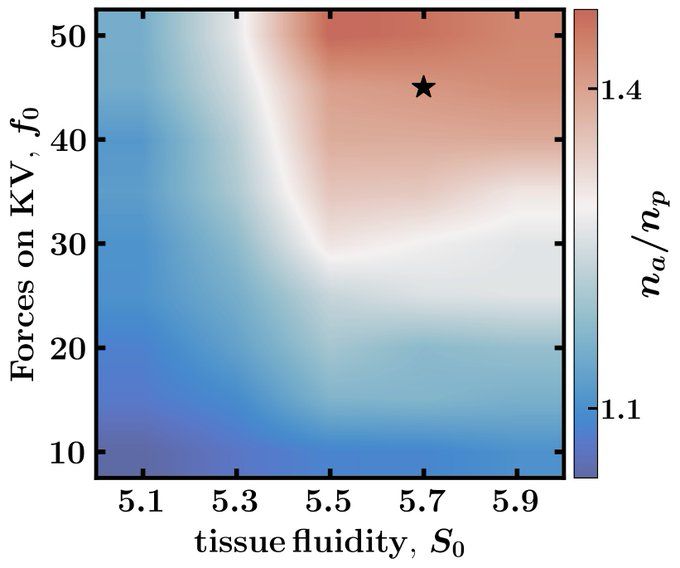

In simulations, we mimic notochord (posterior cell) ablations by removing the pushing (pulling) forces, and find that the organ changes it shape significantly.

9/n

In simulations, we mimic notochord (posterior cell) ablations by removing the pushing (pulling) forces, and find that the organ changes it shape significantly.

9/n

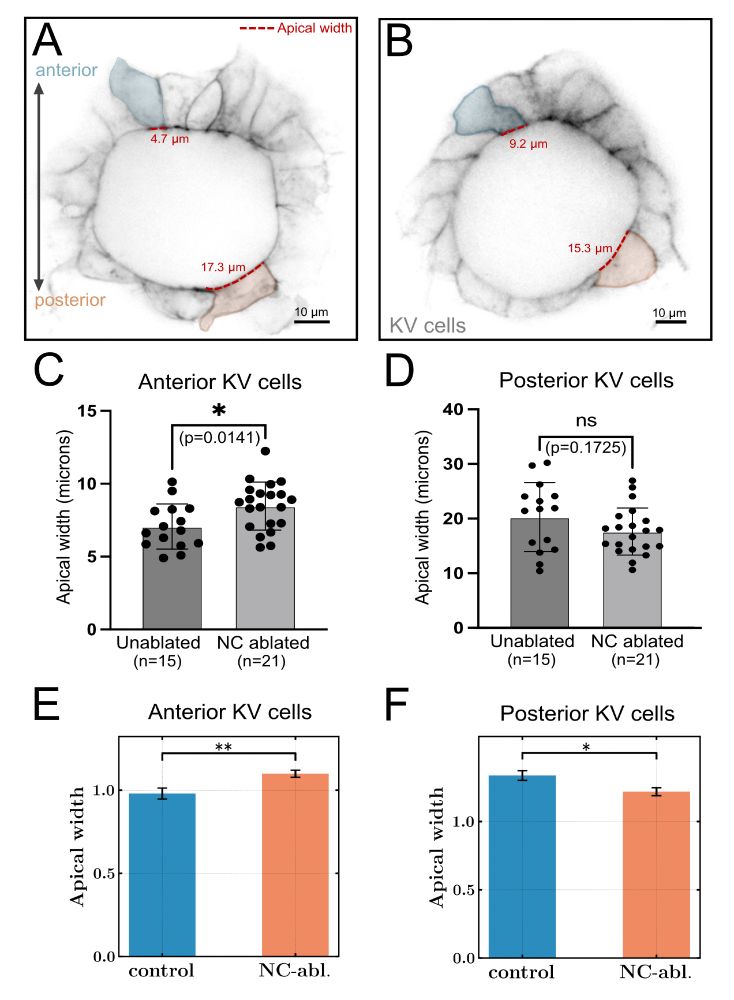

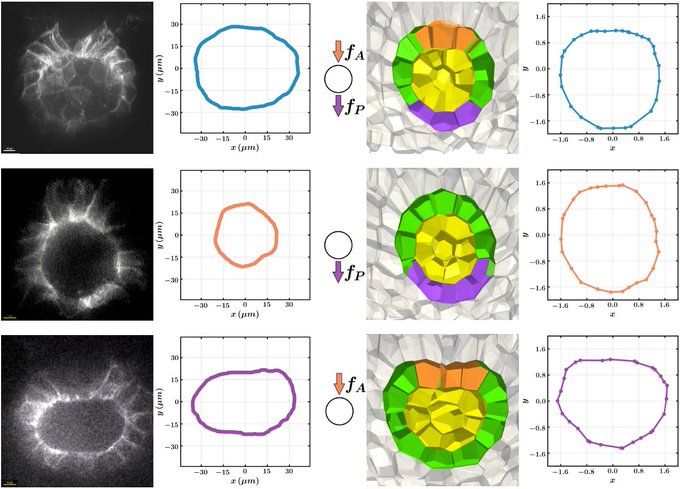

We next ask how these reduced forces affect the shape of the KV lumen and KV cells

7/n

We next ask how these reduced forces affect the shape of the KV lumen and KV cells

7/n

1) quantify how perturbing structures around KV impact its motion

2) measure cell and organ shape in these cases

3) show that observed in vivo shape changes match those predicted from the 3D model

6/n

1) quantify how perturbing structures around KV impact its motion

2) measure cell and organ shape in these cases

3) show that observed in vivo shape changes match those predicted from the 3D model

6/n

5/n

5/n

nature.com/articles/s41...

4/n

nature.com/articles/s41...

4/n

3/n

3/n

2/n

2/n