Webpage: https://www.jeffreyyusof.com/

www.nber.org/papers/w32712

[14/14]

www.nber.org/papers/w32712

[14/14]

nber.org/papers/w31974

[13/14]

nber.org/papers/w31974

[13/14]

In other projects…

[12/14]

In other projects…

[12/14]

Link to paper: bit.ly/40y8XGM

[11/14]

Link to paper: bit.ly/40y8XGM

[11/14]

We find that our experimental measures of fairness preferences are a strong predictor of support for welfare policies (controlling for SES and political affiliation).

[10/14]

We find that our experimental measures of fairness preferences are a strong predictor of support for welfare policies (controlling for SES and political affiliation).

[10/14]

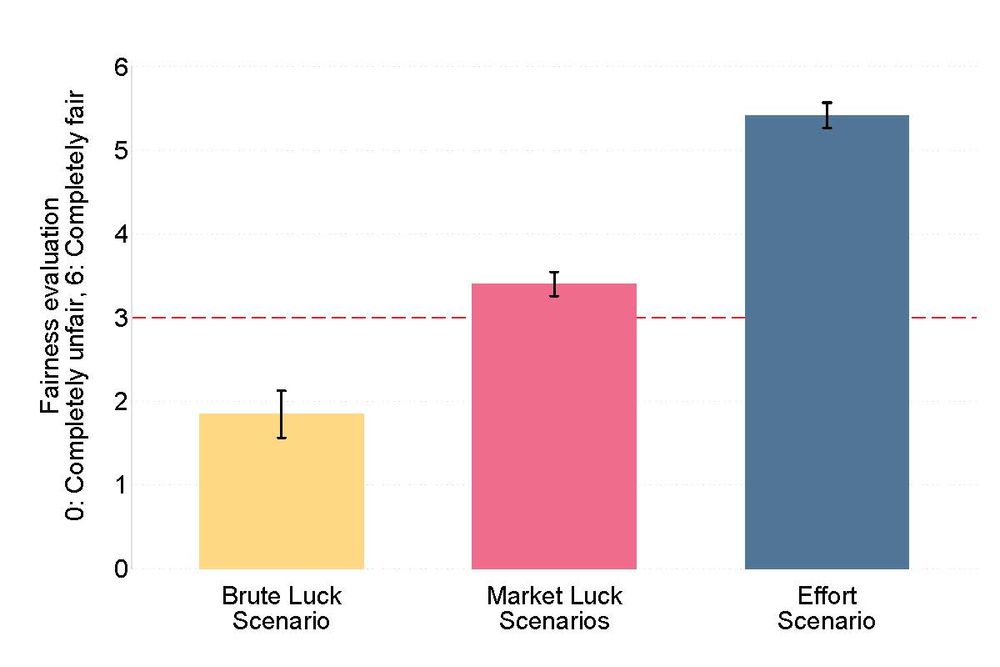

In a complementary vignette study based on real-world scenarios, we again find that individuals perceive inequalities as fairer when caused by external market shocks rather than by brute luck.

[9/14]

In a complementary vignette study based on real-world scenarios, we again find that individuals perceive inequalities as fairer when caused by external market shocks rather than by brute luck.

[9/14]

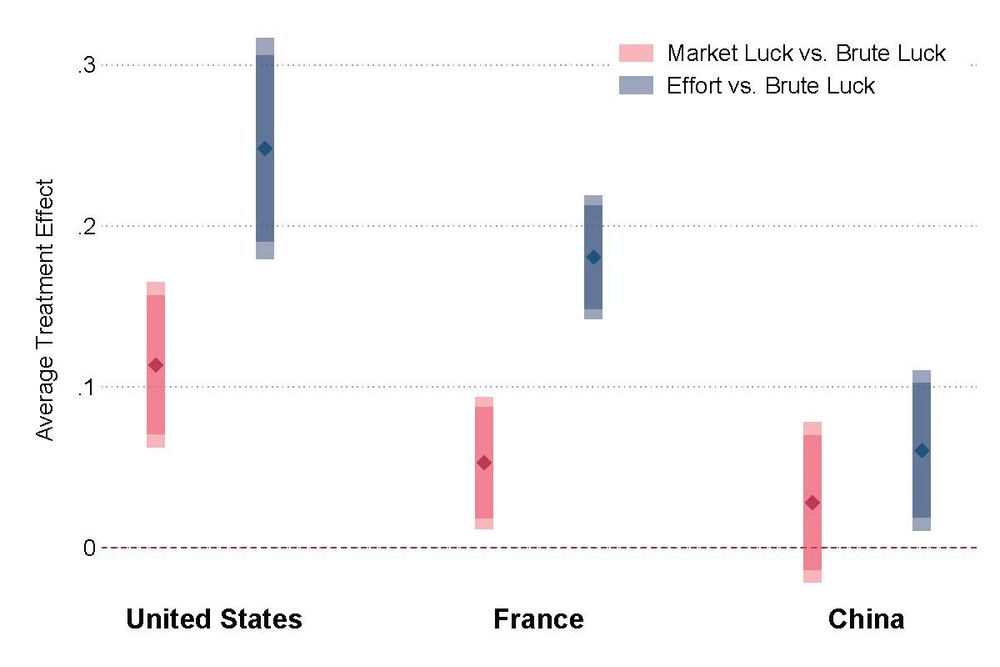

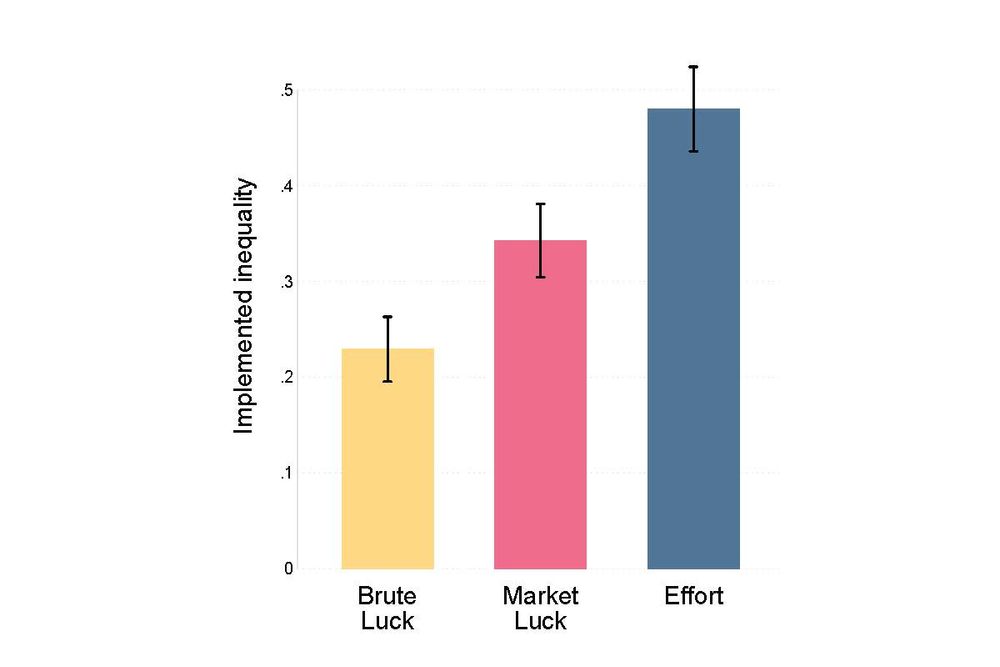

We ran additional experiments in France and China (N=3,500).

The order of implemented inequality is consistent across all countries (bl<ml<ef), but the magnitude of the market luck effect varies.

[8/14]

We ran additional experiments in France and China (N=3,500).

The order of implemented inequality is consistent across all countries (bl<ml<ef), but the magnitude of the market luck effect varies.

[8/14]

– Mere presence of the buyer alone cannot explain the market luck effect.

– Workers’ deservingness increases when they generate a profit for the buyer.

[7/14]

– Mere presence of the buyer alone cannot explain the market luck effect.

– Workers’ deservingness increases when they generate a profit for the buyer.

[7/14]

Spectators implement 50% more inequality (Gini coef) in the market luck treatment than in the brute luck treatment—about half of the effort treatment effect.

This difference mirrors the inequality gap between Denmark and the U.S.!

[6/14]

Spectators implement 50% more inequality (Gini coef) in the market luck treatment than in the brute luck treatment—about half of the effort treatment effect.

This difference mirrors the inequality gap between Denmark and the U.S.!

[6/14]

Here, effort levels are no longer fixed; instead, relative performance on the task determines which worker receives the high income.

[5/14]

Here, effort levels are no longer fixed; instead, relative performance on the task determines which worker receives the high income.

[5/14]

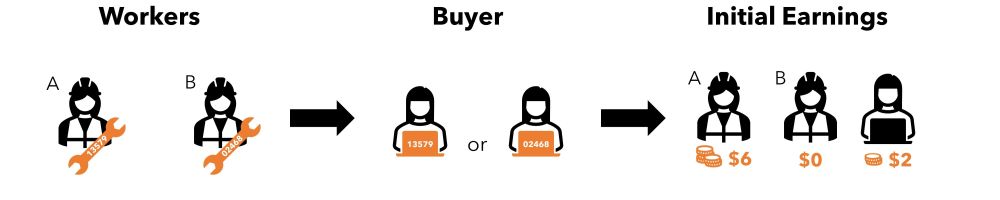

Key points:

1. In both treatments, which worker receives the high income is entirely random.

2. All workers provide the same level of effort.

[4/14]

Key points:

1. In both treatments, which worker receives the high income is entirely random.

2. All workers provide the same level of effort.

[4/14]

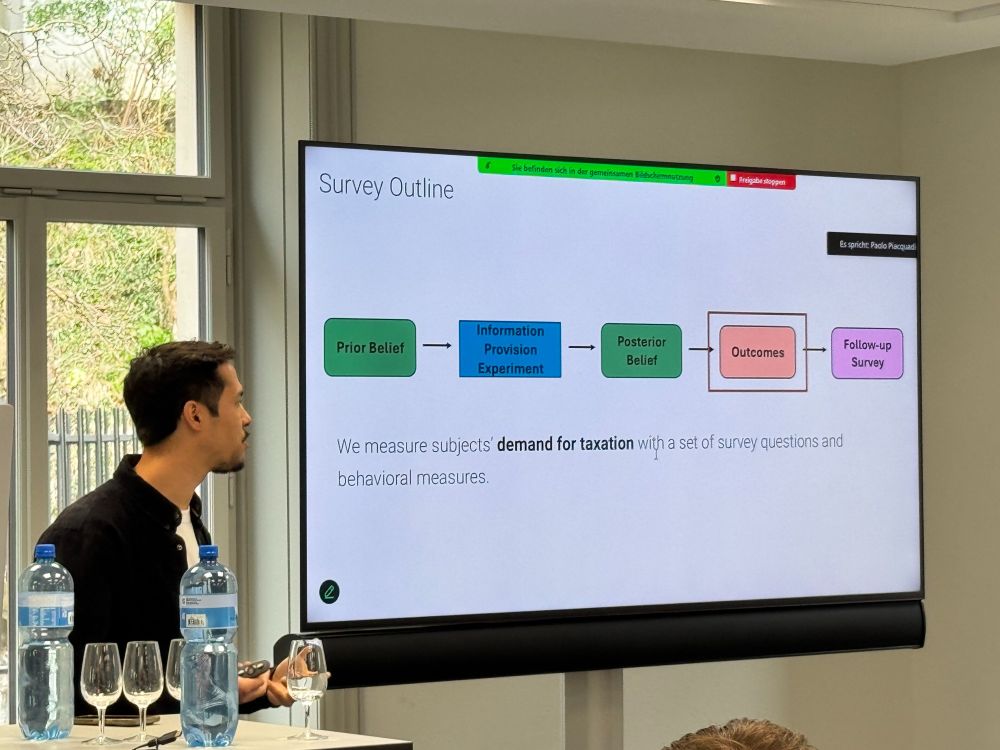

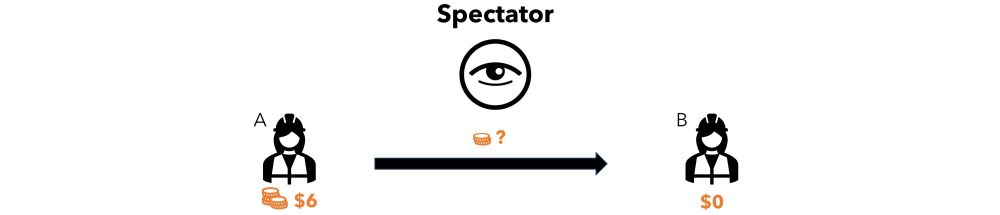

Our main outcome variable is the redistributive choices of nearly 2,000 subjects from the general U.S. population, who act as third-party spectators.

[3/14]

Our main outcome variable is the redistributive choices of nearly 2,000 subjects from the general U.S. population, who act as third-party spectators.

[3/14]

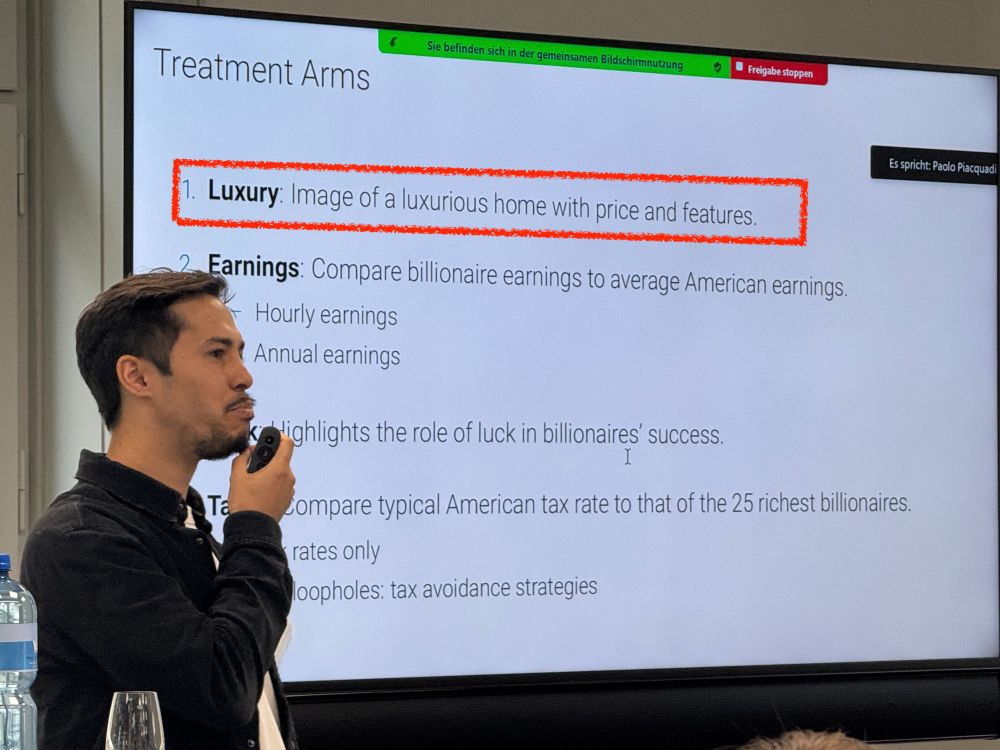

By randomly matching workers with buyers who require specific skills, we generate income inequalities driven by *market luck*.

[2/14]

By randomly matching workers with buyers who require specific skills, we generate income inequalities driven by *market luck*.

[2/14]

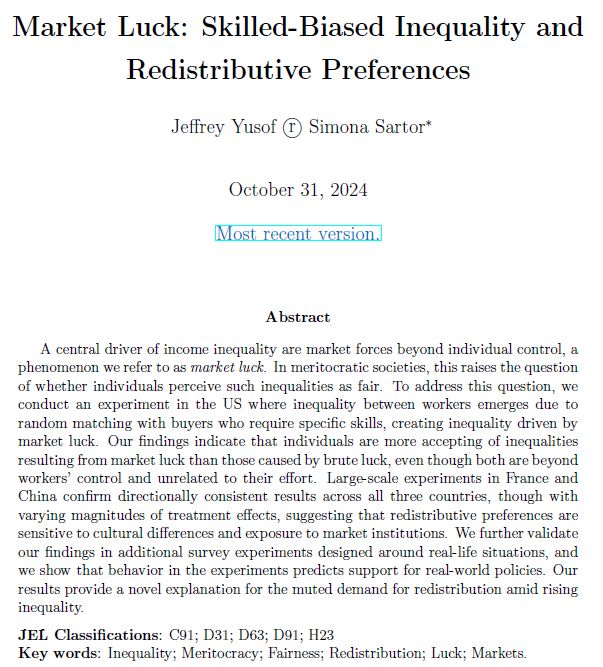

A significant part of inequality stems from market forces beyond individual control - what we call *market luck*.

In meritocratic societies, this raises a key question: Do people perceive these inequalities as fair? [1/14]

A significant part of inequality stems from market forces beyond individual control - what we call *market luck*.

In meritocratic societies, this raises a key question: Do people perceive these inequalities as fair? [1/14]