he/him/his

(I am still surprised whenever I see a particularly old article transliterate the word as 𝘴𝘸𝘵𝘯.)

(I am still surprised whenever I see a particularly old article transliterate the word as 𝘴𝘸𝘵𝘯.)

The verb 𝘣ȝ "have power" is a 2-rad. verb and wouldn't typically have a final -𝘵.

The verb 𝘣ȝ "have power" is a 2-rad. verb and wouldn't typically have a final -𝘵.

Egyptologists often call this sign the “bad bird.”

Egyptologists often call this sign the “bad bird.”

Because of this, the flamingo 𓅟 is used as a triliteral phonological sign representing ⟨dšr⟩, usually found in 𝘥𝘴̌𝘳 “red” and related words.

Because of this, the flamingo 𓅟 is used as a triliteral phonological sign representing ⟨dšr⟩, usually found in 𝘥𝘴̌𝘳 “red” and related words.

This is because 𝘏̣𝘳(𝘸) /ˈħaru(w)/ ("Horus," Greek Ὧρος), who was depicted as a falcon or falcon-headed being, served as a prototype deity.

This is because 𝘏̣𝘳(𝘸) /ˈħaru(w)/ ("Horus," Greek Ὧρος), who was depicted as a falcon or falcon-headed being, served as a prototype deity.

This sign is often found at the end of words because the standard plural endings in Ancient Egyptian were -𝘸 and -𝘸𝘵 for masculine and feminine nouns, respectively.

This sign is often found at the end of words because the standard plural endings in Ancient Egyptian were -𝘸 and -𝘸𝘵 for masculine and feminine nouns, respectively.

In the Old Kingdom, this sign probably represented a uvular trill /ʀ/, but by the Middle Kingdom, the underlying sound had shifted to a glottal stop /ʔ/.

In the Old Kingdom, this sign probably represented a uvular trill /ʀ/, but by the Middle Kingdom, the underlying sound had shifted to a glottal stop /ʔ/.

But if we *really* want to force it, I would probably lean towards something like 𓊪𓏏𓇯𓍿𓎛𓋥𓈖𓏏 𝘱𝘵 𝘵̱𝘩̣𝘯𝘵 “gleaming sky” or “sky of faience.”

But if we *really* want to force it, I would probably lean towards something like 𓊪𓏏𓇯𓍿𓎛𓋥𓈖𓏏 𝘱𝘵 𝘵̱𝘩̣𝘯𝘵 “gleaming sky” or “sky of faience.”

What is that element at the top of the new sign? That’s right, it’s the 𓇯 𝘱𝘵 “sky” sign!

What is that element at the top of the new sign? That’s right, it’s the 𓇯 𝘱𝘵 “sky” sign!

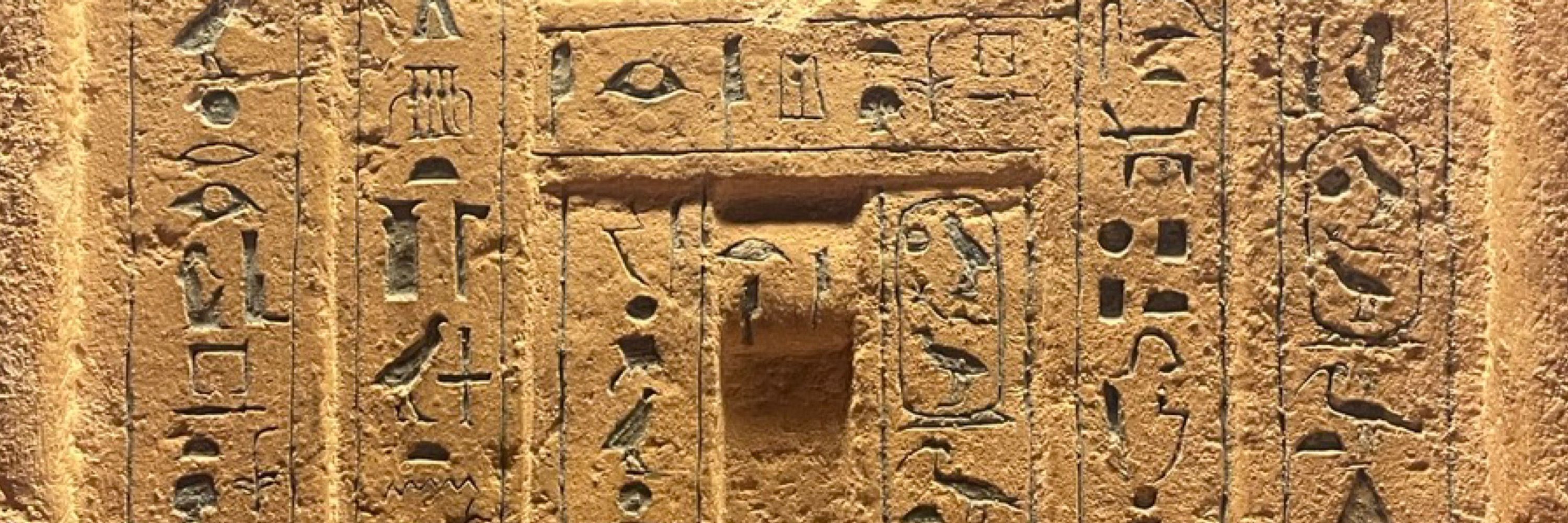

As an illustration, here is a Late Period inlay of the 𓇯 𝘱𝘵 “sky” sign (N1) made of faience, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (26.3.164i).

As an illustration, here is a Late Period inlay of the 𓇯 𝘱𝘵 “sky” sign (N1) made of faience, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (26.3.164i).

The word for “faience” 𓍿𓎛𓋥𓈖𓏏𓈒𓏥 𝘵̱𝘩̣𝘯𝘵 is derived from the verb 𓍿𓎛𓈖𓋥 𝘵̱𝘩̣𝘯 “to gleam, dazzle.”

The word for “faience” 𓍿𓎛𓋥𓈖𓏏𓈒𓏥 𝘵̱𝘩̣𝘯𝘵 is derived from the verb 𓍿𓎛𓈖𓋥 𝘵̱𝘩̣𝘯 “to gleam, dazzle.”

An early example in the Pyramid Texts is 𝘫ꜥ 𝘩̣𝘳 𝘱𝘵 𝘣ȝ𝘲 𝘱𝘥̱𝘵 “The face of the sky has been washed. The expanse is bright/clear” (PT 570 §1443a).

An early example in the Pyramid Texts is 𝘫ꜥ 𝘩̣𝘳 𝘱𝘵 𝘣ȝ𝘲 𝘱𝘥̱𝘵 “The face of the sky has been washed. The expanse is bright/clear” (PT 570 §1443a).

For example, although 𝘸ȝ𝘥̲ “green” overlaps a bit with what we consider blue, it (as far as I can tell) is never used to describe the sky.

For example, although 𝘸ȝ𝘥̲ “green” overlaps a bit with what we consider blue, it (as far as I can tell) is never used to describe the sky.

The most famous example of this is probably the Homeric Greek expression οἶνοψ πόντος “wine-faced sea.” As a comparison, Egyptians called the sea 𝘸ȝ𝘥̱-𝘸𝘳 “Great Green.”

The most famous example of this is probably the Homeric Greek expression οἶνοψ πόντος “wine-faced sea.” As a comparison, Egyptians called the sea 𝘸ȝ𝘥̱-𝘸𝘳 “Great Green.”

“Blue” is more difficult, as the Egyptian languages don’t really have a word for what we call “blue.”

“Blue” is more difficult, as the Egyptian languages don’t really have a word for what we call “blue.”