https://research.pasteur.fr/en/team/evolutionary-cell-biology-and-evolution-of-morphogenesis/

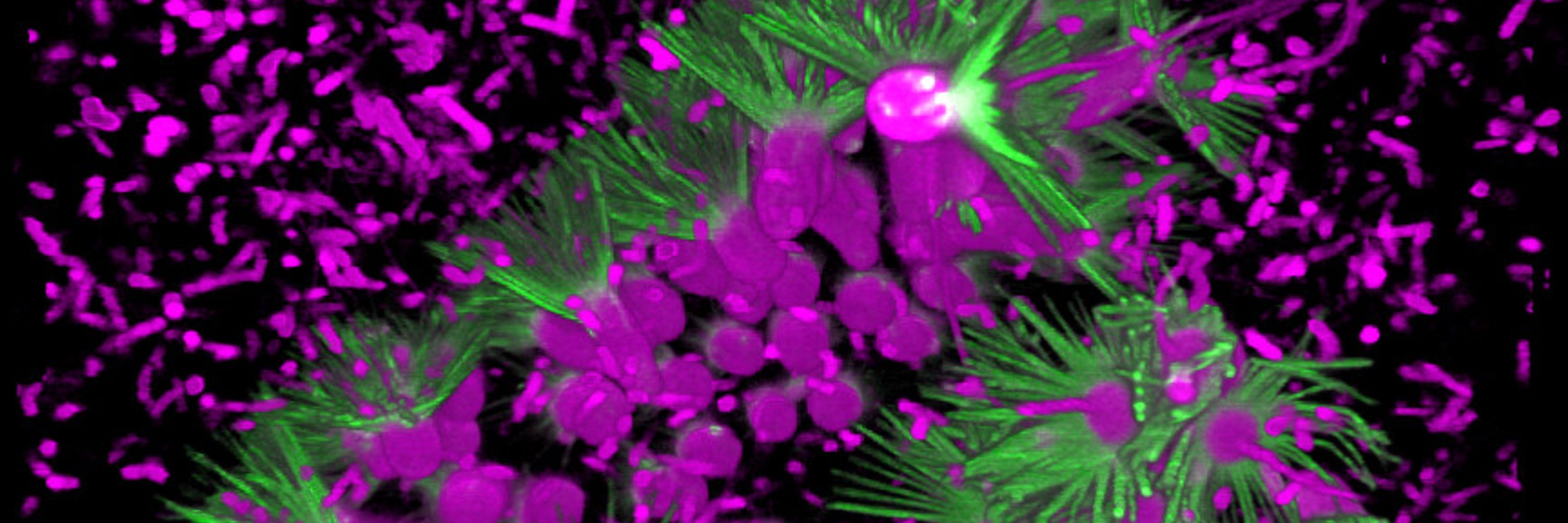

This suggests the molecular pathways that control multicellular development in animals and choanos might be more conserved than we expected...

This suggests the molecular pathways that control multicellular development in animals and choanos might be more conserved than we expected...

The genes were known to be conserved in choanos...

The genes were known to be conserved in choanos...

This is two stories in one: a case study/cautionary tale on developing genetic tools in new organisms, and the first hint at a gene regulatory network for choanoflagellate multicellular development (which turn out to involve a Hippo/YAP/ECM loop!) A 🧵

This is two stories in one: a case study/cautionary tale on developing genetic tools in new organisms, and the first hint at a gene regulatory network for choanoflagellate multicellular development (which turn out to involve a Hippo/YAP/ECM loop!) A 🧵